Using AI to Respond to Written Discovery Requests - Part 1

Artificial intelligence tools help you get work done faster and better at every stage of a lawsuit – a topic I have been addressing in an ongoing series of posts.

Today’s post is part 1 of a two-part discussion. This part goes addresses written discovery requests and response and their components. Part 2 will look at ways to use AI as you prepare written responses to interrogatories, requests for production of documents, and requests for admission.

Earlier posts in the series are:

- AI Across the Life of a Lawsuit

- Using AI to Prepare Complaints: Part 1, The Complaint

- Using AI to Prepare Complaints: Part 2, The AI

- Using AI to Prepare the Answer to a Complaint

- Using AI to Prepare for Depositions

As a litigation attorney, I wrote over 10,000 responses to interrogatories, requests for production of documents, and requests for admission. This type of work is done every day by tens if not hundreds of thousands of attorneys throughout the US.

Requesting parties use interrogatories, document requests, and requests for admission to gather information, lock in opposing parties, and on occasion deliver messages. Responding parties make strategic use of these tools as well. They use them, for example, to help provide others with information that the responding parties then can use to shape the story of the case. They also deploy them to convey targeted messages to the requesting parties, other participants in the lawsuit, the court, and even people or organizations not formally including in the case.

Because the requests and responses are written as opposed to oral, those composing them can spend the time to craft them carefully. This careful crafting can mean precision targeting. It also, however, can mean that much of the information received is of limited value. Nonetheless, written discovery long has been and will continue to be a valuable tool.

A Framework and Three Caveats

I will start with an examination of the three tools that make up most of written discovery, each defined and described by a rule from the U.S. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. If you want, feel free to jump to the latter part of this post where I give three examples of how you can use AI to gather information potentially useful in determining how to respond to written discovery requests.

Three key FRCP rules and their attendant tools are:

- Rule 33. Interrogatories to Parties

- Rule 34. Producing Documents, Electronically Stored Information, and Tangible Things, or Entering onto Land, for Inspection and Other Purposes

- Rule 36. Requests for Admission

At this point I need to raise three important caveats. First, in this post I only am addressing civil matters, not criminal ones. Second, in any discussion about how discovery is approached, we should remember that each state has its own rules of civil procedure. Many sets of state civil procedural rules track the federal ones closely. Some states, notably Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and New York, differ in ways small and large. Finally, much of the rest of the world approaches discovery quite differently from the United States.

The Formal Tools

Interrogatories

An interrogatory is a written question one party sends to another during the discovery process. Interrogatories usually are sent in sets. “Plaintiff’s First Set of Interrogatories to Defendant”, for example, might be a single set of interrogatories consisting of 10 separate questions.

Posing Interrogatories

A requesting party writes a set of one or more interrogatories and serves those interrogatories on the responding party.

In theory, each interrogatory addresses a single topic.

The scope of the topic might be tightly focused, it could be very broad, or anywhere in between. Rule 26(b) sets the boundaries for discovery, including for interrogatories. According to that rule, parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter provided it meets two requirements.

First, the information sought must be relevant to any party’s claims or defenses. Second, the process of obtaining the information must be proportional to the needs of the case. Proportionality is determined by considering six factors:

- The importance of the issues at stake in the action,

- The amount in controversy,

- The parties’ relative access to relevant information,

- The parties’ resources,

- The importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, and

- Whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit.

The rule does not say how much weight to apply to each of these factors.

Information within this scope of discovery can be discoverable even if it is not admissible in evidence.

By default, in federal cases the number of interrogatories is limited to 25. If an interrogatory has subparts, each discrete subpart counts as a separate interrogatory.

Responding to Interrogatories

The responding party responds to the interrogatories using a written document. It might call its response to the above requests something like “Defendant’s Responses to Plaintiff’s First Set of Interrogatories to Defendant”.

The responding party has a set of amount of time in which to respond, 30 days by default.

Parties responding to interrogatories do so under oath. Usually attorneys write the responses, working from information they gather from their clients and elsewhere. This tends to lead to carefully created responses.

The responding party has four basic options for how to respond to each interrogatory:

- Answer the interrogatory.

- Object to the interrogatory, stating the objection or objections with specificity. Generally, if the responding party does not state an objection at this point in the process, that party waives the objection.

- Answer in part and object in part.

- If the answer to the interrogatory can be determined by reviewing the responding party’s business records and if the review would be impose a substantially similar burden for both parties, (a) specify which document should be reviewed and (b) give the requesting party a reasonable opportunity to examine and audit the records and make copies, compilations, abstracts and summaries.

Document Requests

A document request is a written request for documents or electronically stored information (ESI) that one party sends to another during the discovery process. (Rule 34 also applies to tangible objects and land or other property, something I will not address here.)

Like interrogatories, document requests also usually come in sets such as “Plaintiff’s First Set of Requests for Production of Documents to Defendant”. Unlike interrogatories, there is no default limit on the number of document requests one party may serve on another party.

Posing Document Requests

A requesting party may serve a Rule 34 document request on any party.

The scope of the information a party may discover via document requests is the same as the scope for interrogatories.

A requesting party may ask a responding party to:

- Produce designated documents to the requesting party;

- Permit the requesting party or its representative to inspect, copy, test, or sample designated documents;

- Produce designated ESI to the requesting party; and

- Permit the requesting party or its representative to inspect, copy, test, or sample designated ESI.

With respect to documents and ESI, the requesting party:

- Must describe with reasonable particularity each item or category of items to be inspected;

- Must specify a reasonable time, place, and manner for the inspection and for performing the related acts; and

- For ESI, may specify the form or forms in which electronically stored information is to be produced.

Responding to Document Requests for Admission

Generally, the responding party has 30 days in which to respond under oath to the document requests.

The responding party is supposed to respond to each requested item or category separately. For each item or category, the responding party must either (1) state in writing that inspection and related activities will be permitted as requested or (2) object in writing to that specific request and state with specificity the grounds and reasons for objecting.

Instead of permitting inspection, the responding party may elect to produce copies of documents or ESI.

The same deadlines apply, whether the responding party opts for inspection or production.

For ESI, the responding party may object to the form or forms of production specified by the requesting party. If the responding party objects, it must state the form or forms it intends to use. If the requesting party did not specify its desired form or forms of production, the responding party must state the form or forms it intends to use.

When producing documents or ESI, the responding party theoretically either must produce those materials as they are kept in the ordinary course of business or must organize and label them to correspond to the categories of the request.

Among more sophisticated and experienced parties, the preferred approach is to produce ESI as some combination of:

- Native files;

- Files that have been converted to an image form, typically TIFF or PDF; extracted text;

- Extracted metadata; and

- A specialized file called a load file that allows the recipient to stitch the native files, image files, text, and metadata together in a way that allows easy use of the content.

Challenge Responses to Requests for Admission

Upon receiving responses to requests for admission, the requesting party bring a motion asking the court to determine the sufficiency or an answer or objection.

Objections

Parties are entitled to object to discovery demands.

Federal rules require that parties making objections specifically state the grounds for their objections, rather than using boilerplate language such as objecting “to the extent that the request is overly broad and unduly burdensome”. Rule 33(b)(4) requires that a party objecting to an interrogatory state the grounds for its objections with specificity. Rule 36(a)(5) requires that a party objecting to a request for admission state the grounds for objecting. Under Rule 34(b)(2), a party objecting to a document request needs to:

- State with specificity its grounds for objecting to the request,

- Include its reasons,

- State whether it was withholding any responsive materials on the basis of the objection, and

- State when it will produce responsive materials.

In addition to being required by federal civil procedural rules, stating objections clearly and specifically is good practice.

Objections typically appear in written discovery responses in two ways.

General Objections

It long has been common for responding parties to include a section in their responses, often entitled “General Objections” or something similar, where they lay out objections applicable to all the requests in a set. General objections should be, as noted in commentary from The Sedona Conference, “very limited.” As been remarked by several courts, “general objections are considered ‘overly broad and worthless unless the objections are substantiated with detailed explanations.’”

Objections to Specific Requests

Parties also assert objections in response to specific discovery requests.

Objection Strategies

Whether asserting a general objection or a specific one, it is prudent to offer an alternative. For example, a party might respond to a request seeking documents from an unstated period of time by objecting to the open time frame and saying that it will produce documents discussing events that occurred between date A and date B.

With a little searching, you can find helpful lists of discovery objections and acceptable ways to frame them. One such list is for cases assigned to Lauren Louis, a magistrate judge in the Southern District of Florida. It discusses more effective alternatives to common boilerplate objections “vague, overly broad and unduly burdensome” and “irrelevant or not reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence”, and objections based on scope or privilege, and formulaic objections followed by an answer.

The Structure

Interrogatories, documents requests, and requests for admission share a common structure. Here are key elements you are likely to see:

Caption

Requesting and Responding

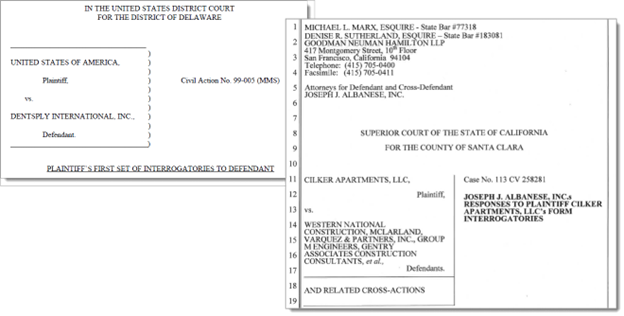

The caption gives you a thumbnail of the case, of sorts. You may see, among other things:

- Names of some or all the parties,

- Names of and additional information about the parties’ attorneys,

- Name and location of the court handling the matter,

- Case number and whether this is a civil or criminal action,

- Title of the pleading.

Here are two examples:

Initial Statement

Requesting and Responding

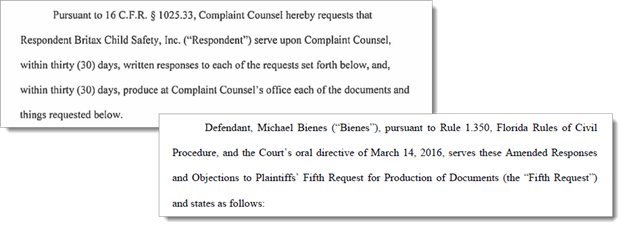

Written discovery requests and responses often contain an initial paragraph that gives the reader a quick understanding of what is to follow. Here are two examples, the first from a request for production of documents and the second from a response to set of document requests.

Definitions

Requesting and Responding

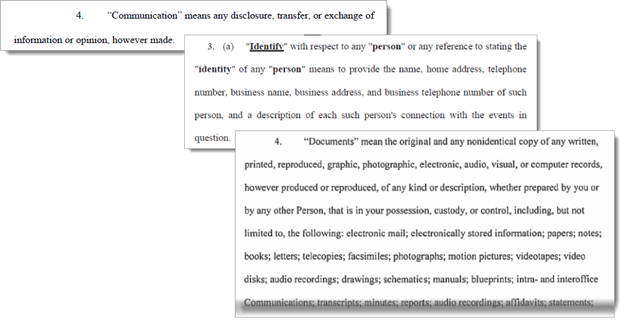

In requests and occasionally in responses, parties often define some of the terms they use. More commonly defined words and phrases include “document”, “person”, “identify”, and “you”. The discovery requests from which I draw examples here contained 3, 12, 18, 22, and 23 definitions – not counting subparts.

Here are three examples from those documents:

After you have read – or prepared - enough written discovery requests and responses, you will come to appreciate that these definitions are as like as not “more honour’d in the breach than the observance.”

Instructions

Requesting

Requesting parties also frequently include instructions. The instructions might set parameters, as with this example:

Sometimes instructions describe expectations about what is and is not included in a response or production, as with this instruction about what constitutes a document:

Often, instructions have more than a hint of attempting to cover all bases, such as this common direction:

General Objections

Responding

If asserted, general objections usually are placed immediately after definitions and instructions. Here is an example of the beginning of a “General Objections” section:

Individual Requests

Requesting

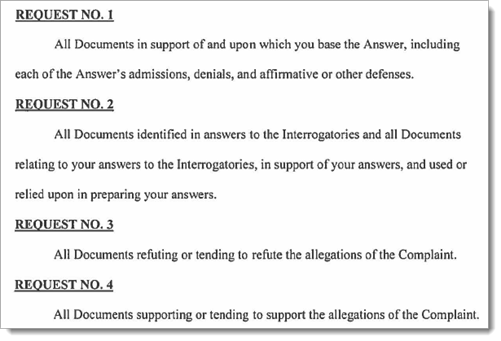

Individual requests usually are numbered sequentially. In theory, each request should focus on a specific topic and should be self-contained. Here is an example of the first few requests in a set of document requests:

Individual Responses and Objections

Responding

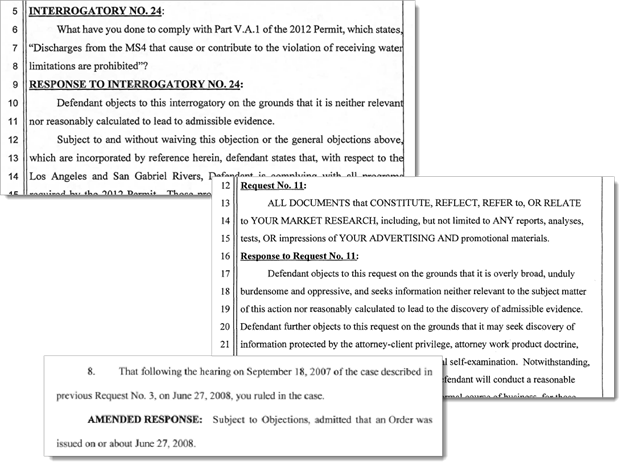

Each request is responded to separately. Some attorneys simply state the responses. The better practice is to repeat the request and then provide the response.

If specific objections are asserted, they usually are stated first, followed by substantive responses.

Here are three examples (replete with boilerplate objections):

Part 2 Review

With its fact-finding and analytics functions, AI can help you respond to discovery demands faster, better, and cheaper. Here are some examples of how you might accomplish that.

The core blocking and tackling of responding to interrogatories, production requests, and requests for admissions focuses on two areas: (1) answering and (2) objecting. Both for answering and for objecting, there are two key sources of information to consider: (1) discovery documents and data and (2) past discovery requests and responses.

In Part, I will share examples of what how you can use AI to search for content that might help in determining how to respond to written discovery requests.

Try AI for Your Next Discovery Responses

With the right AI-driven platform, you can prepare responses to written discovery requests better, faster, and cheaper – cconfident that you are serving your client well.

If your organization is interested in learning more about making more effective use of AI across the life of a lawsuit and find out how Reveal uses AI as an integral part of its AI-powered end-to-end legal document review platform, please contact us.