Using AI to Prepare Complaints: Part 1, The Complaint

Artificial intelligence tools can deliver great value at every stage of a lawsuit, something we discussed at a high level in AI Across the Life of a Lawsuit.

Today we begin to dig in more deeply, starting with how you can use AI technology to good advantage at one of the earliest steps in a new case, preparing the complaint. Because of the piece’s length, we are dividing it into two parts. Today’s part focuses on the complaint itself. The next part examines how you can use AI to do a better job of preparing the complaint.

Once again, we will use the US Federal system as our guiding framework.

In broad terms, the earliest days of a lawsuit typically can look similar to this:

- Something happens that, according to the potential plaintiff, harmed the plaintiff.

- The potential plaintiff approaches a lawyer (that's you), hoping the lawyer will be able to deliver some form of satisfaction.

- You conduct an initial investigation to determine whether, among other things, (a) the potential plaintiff appears to have an actionable case, (b) at least one viable defendant can be sued, and (c) there is a realistic change of success.

- If the answers to these and similar questions are yes, you prepare a summons and complaint that gets served on the defendant.

- And the lawsuit begins.

There are many other steps you also will need to undertake. These include running a conflicts check, determining whether your potential client will be able to pay any necessary fees, decided whether representing this particular client could harm your representation, formally agreeing to represent the client, perhaps attempting to settle the matter before suing it out. Those are topics for another forum.

Elements of a Complaint

In the Federal system, a complaint need only contain three elements:

- A short and plain statement of the grounds for the court’s jurisdiction;

- A short and plain statement of each of the plaintiff’s claims against the defendant, showing that the plaintiff is entitled to relief; and

- Demand for the relief sought. (See Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 8(a)).

Complaints usually contain more than just those three elements. A common structure may include at least the following:

- Caption;

- Initial statement of the case;

- Parties;

- Grounds for jurisdiction;

- Grounds for the venue;

- Statement of claims or facts;

- Causes of action; and

- Demand for relief.

As you go through this process, you can use AI systems to assist and guide you, perhaps in ways, you have not considered before.

Preliminary Investigations

A duty to investigate

Before you sue out a new case, you have a responsibility to conduct a reasonable investigation, a topic discussed in, for example, at 2021 ABA Journal article, What is a lawyer's ethical duty to check out a client's claim before filing an action?

FRCP 11(b)(3) imposes on lawyers a duty to ascertain that factual contentions they set forth in a complaint have or are likely to have evidentiary support:

By presenting to the court a pleading, written motion, or other paper - whether by signing, filing, submitting, or later advocating it - an attorney or unrepresented party certifies that to the best of the person's knowledge, information, and belief, formed after an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances...the factual contentions have evidentiary support or, if specifically so identified, will likely have evidentiary support after a reasonable opportunity for further investigation or discovery...

Several of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct come into play as well. Pursuant to Rule 3.1: Meritorious Claims & Contentions, lawyers must have sound factual bases for proceedings they bring:

A lawyer shall not bring or defend a proceeding, or assert or controvert an issue therein unless there is a basis in law and fact for doing so that is not frivolous, which includes a good faith argument for an extension, modification, or reversal of existing law.

The second comment to Rule 3.1 expands on this:

The filing of an action or defense or similar action taken for a client is not frivolous merely because the facts have not first been fully substantiated or because the lawyer expects to develop vital evidence only by discovery. What is required of lawyers, however, is that they inform themselves about the facts of their clients' cases and the applicable law and determine that they can make good faith arguments in support of their clients' positions.

Similarly, Rule 4.1, Truthfulness in Statements to Others, states that "[i]n the course of representing a client a lawyer shall not knowingly...make a false statement of a material fact or law to a third person...."

Conducting a Reasonable Factual Investigation

What constitutes - or should constitute - a reasonable factual investigation has changed with the advent and expansion of eDiscovery.

When I started practicing law in the 1980s, conducting initial factual investigations often meant:

- Meeting with the prospective client;

- Where applicable, meeting with additional people involved in or with knowledge of the events leading to the alleged damages;

- Gathering a limited number of documents from the client and others - often less than a box's worth - and going through those documents; and

- Possibly obtaining documents from third parties, such as getting copies of a client's medical records, and examining those documents.

Talking with a few people and looking at a box of documents is no longer enough. Personal computers, mobile devices, social media accounts, and the multitudinous forms of electronic communications we now use have changed initial factual investigations considerably. A single PC can easily contain a million files. On a matter I worked on recently, we gathered more than 64,000 chat messages from a single client's cell phone. Collectively, every minute we post 458,000 tweets on Twitter, share 527,760 photos on Snapchat, watch 4,146,600 YouTube videos, send 16 million text messages and 165 million emails, and take 45,788 Uber rides.

Even before you bring a new case to court, you will have access to some portion of this new trove of content. Working with that content and finding useful information within it - is another issue.

As you consider whether to initiate a new lawsuit and then as you prepare a complaint, you should have reasonable access to a significant quantity of potentially useful data from your client (or potential client). That can include emails and their attachments; files that have been sent, received, or stored; content posted to or available via social media; photos, videos, and other audiovisual content; and possibly much more.

To make effective use of that content, you first should frame your objectives. As you are drafting a complaint, two common goals are to:

- Find data that tends to support or refute a claim you plan to assert; and

- Find data that suggests a different or stronger case for you to pursue.

Once you have framed your objectives, you should determine which tools you want to use to achieve those objectives. You can use standard approaches to searching such keyword searches to try to hone in on specific desirable content. You also can use standard filtering approaches such as deNISTing to identify and set aside data that is only going to get in your way.

The Complaint and its Parts

For the rest of this post, we are going to work with an actual complaint, one posted on the web by the plaintiff's counsel.

The case, and the complaint, are typical of what I dealt with as a practicing lawyer, both in terms of scope and in terms of size. Plaintiff's counsel brought the matter in federal court in the Central District of California. It is a product liability case in which an individual plaintiff sought compensatory and punitive damages from two related companies, asserting nine causes of action.

The complaint is 37 pages long and contains 126 numbered paragraphs - 159 if you add in subparagraphs and un-numbered paragraphs. To help give context, here is a count of paragraphs by section:

- Introduction: 1 paragraph

- Parties: 11 paragraphs

- Jurisdiction: 2

- Venue: 2

- Factual Background: 30

- First Cause of Action: 12

- Second Cause of Action: 16

- Third Cause of Action: 16

- Fourth Cause of Action: 11

- Fifth Cause of Action: 10

- Sixth Cause of Action: 16

- Seventh Cause of Action: 11

- Eighth Cause of Action: 9

- Ninth Cause of Action: 10

- Prayer for Damages: 1

- Demand for Jury Trial: 1

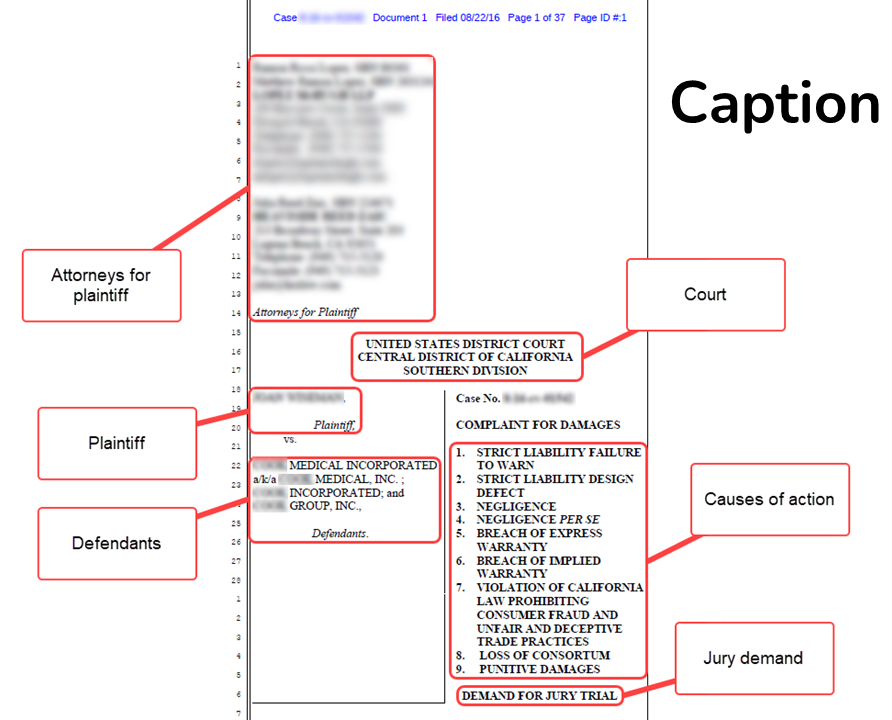

Caption

The caption is the first thing readers see when they look at the complaint. A complaint's caption should include the court's name; a title, which must list all the parties; a file number; and a Rule 7(a) designation. (FRCP Rule 10(a)).

A typical caption may look something like this.

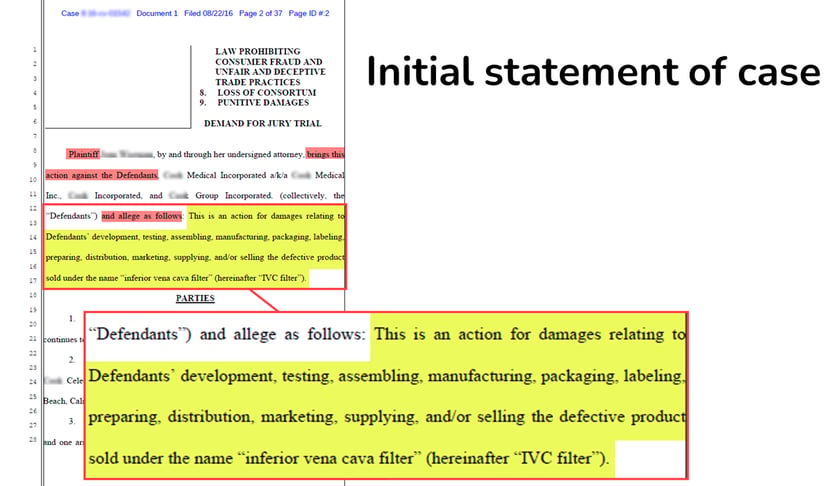

Initial Statement of the Case

The opening paragraph of a complaint contains the first substantive information presented to the reader. This is your chance to make a good first impression.

You can use that paragraph, as the attorneys did in the example below, to succinctly lay out the core of your case. In this example, by the end of the first paragraph the reader knows the basics of who is suing whom, for what, and why.

Because you make your first impression with that initial paragraph, you want to make sure you get everything right. Use the wrong names for the parties, assert that a defendant did something it did not actually do, incorrectly name a product, and winning your case immediately becomes more challenging.

Here, plaintiff's counsel laid out eleven sets of activities for which supporting evidence may eventually need to be provided: development of a product, testing of that product, and so on. Plaintiff's counsel identified the product at issue: an inferior vena cava filter. Plaintiff's counsel named the companies involved. And plaintiff's counsel asserted that the product was defective.

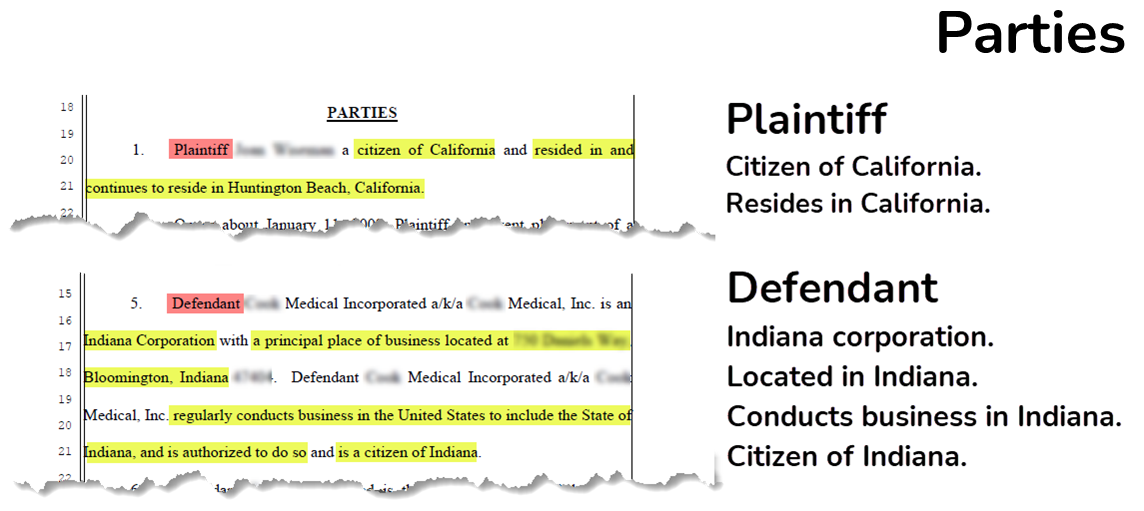

Parties

In the complaint, you need to name all the parties to the suit. Rules 17 though 25 address parties. Plaintiffs bring the case; defendants are the ones being sued by the plaintiffs.

Later in the case, this can become more complicated. A defendant might bring a counterclaim against the plaintiff. The defendant becomes a counter-plaintiff and the plaintiff, a counter-defendant. If one defendant brings a crossclaim against another defendant, the former is the cross-complainant and the latter the cross-defendant. If a defendant brings a third party into the lawsuit, the defendant becomes as third-party plaintiff and the newly added entity becomes and third-party defendant.

The complaint needs to include the name of each party and typically included additional information as well. Here, for example, plaintiff's counsel named the plaintiff, who is stated to be a citizen and resident of California. Plaintiff's counsel also named several defendants and included details such as principle places of business, state of citizenship, and the like.

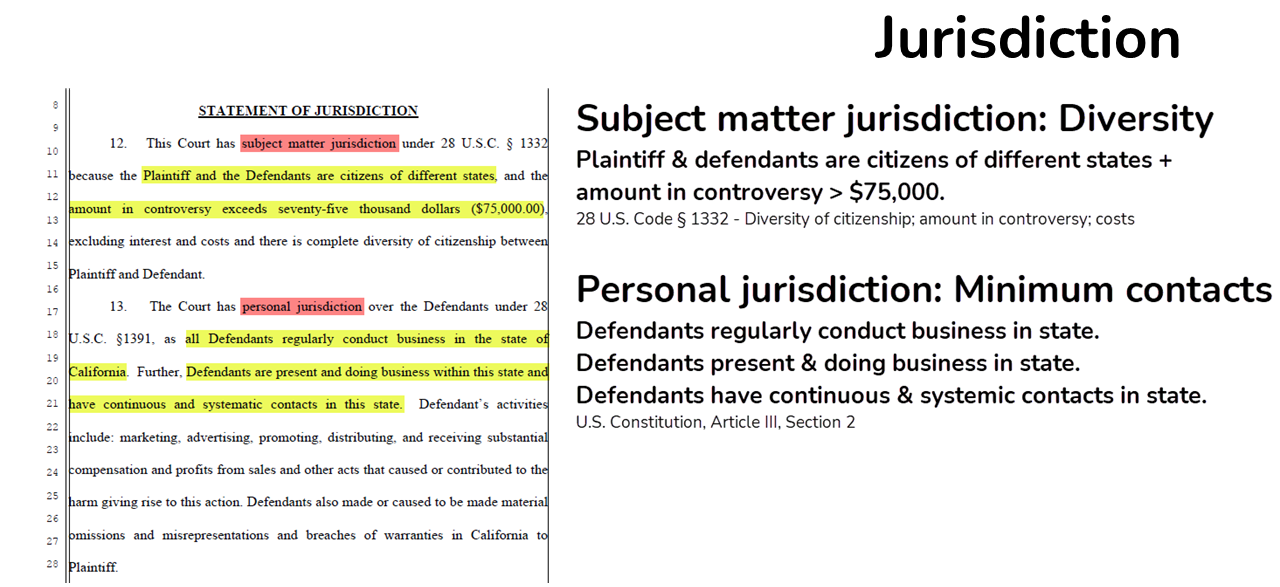

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the power of a court to hear a case.

US district courts have original jurisdiction of all civil matters arising under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States. (28 U.S. Code § 1331.)

US district courts also have original jurisdiction in civil actions where the matter in controversy is greater than $75,000 and there is diversity of citizenship, such as where the case is between citizens of different states. (28 U.S. Code § 1332.)

A complaint must contain "a short and plain statement of the grounds for the court's jurisdiction..." (FRCP Rule 8(a)(1).)

Here, plaintiff's counsel stated two grounds for jurisdiction:

- Subject matter jurisdiction, because the plaintiff and the defendants are citizens of different states and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000; and

- Personal jurisdiction, for multiple reasons: all defendants regularly conduct business in California; defendants are present and doing business in California and have continuous and systematic contacts in California; and defendants made material omissions and misrepresentations and breaches of warranties to plaintiff in California.

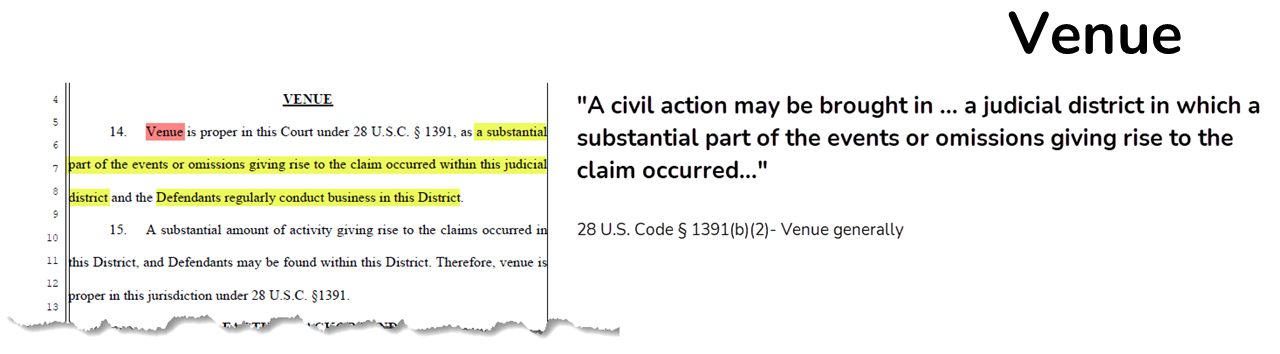

Venue

Venue refers to geography. An appropriate venue is a geographical location where an action may appropriate be brought, such as the Central District of California, Southern Division. The term is defined as:

the geographic specification of the proper court or courts for the litigation of a civil action that is within the subject-matter jurisdiction of the district courts in general, and does not refer to any grant or restriction of subject-matter jurisdiction providing for a civil action to be adjudicated only by the district court for a particular district or districts.

Generally, in any judicial district that meets any of the following three sets of requirements:

(1) a judicial district in which any defendant resides, if all defendants are residents of the State in which the district is located;

(2) a judicial district in which a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred, or a substantial part of property that is the subject of the action is situated; or

(3) if there is no district in which an action may otherwise be brought as provided in this section, any judicial district in which any defendant is subject to the court’s personal jurisdiction with respect to such action.

In this example, plaintiff counsel used 1391(b)(2).

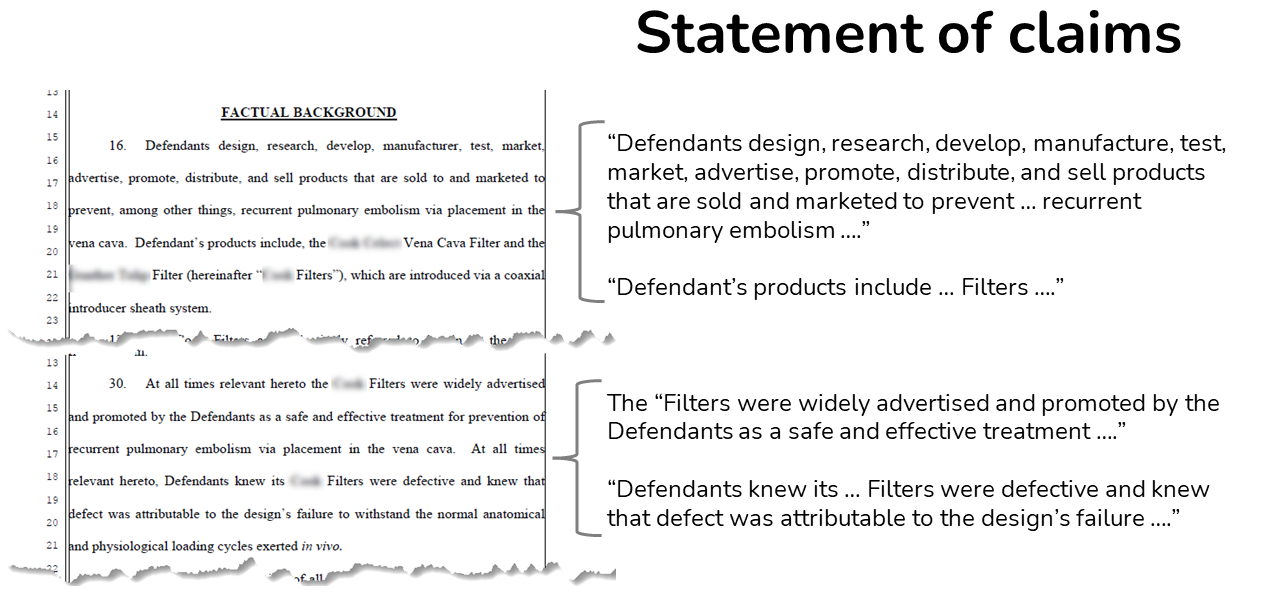

Statement of Claims

A plaintiff's statement of claims summarizes the facts supporting the plaintiff's case.

Plaintiffs are supposed to state claims in numbered paragraph and each paragraph is to be limited, as far as practicable, to a single set of circumstances. (FRCP Rule 10(b)). Our example complaint contains thirty paragraphs in its statement of claims.

Here are two of the paragraphs. Each lays out facts that, presumably, plaintiff's counsel anticipates will need to be proved to win the case.

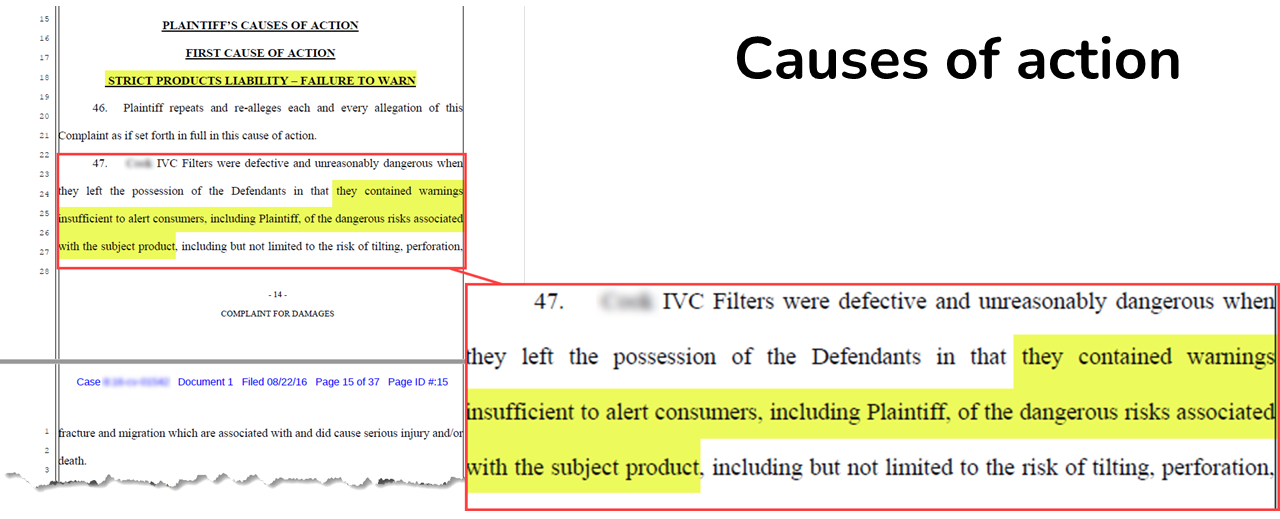

Causes of Action

A cause of action is "[a] set of predefined factual elements that allow for a legal remedy. The factual elements needed for a specific cause of action can come from a constitution, statute, judicial precedent, or administrative regulation." (Legal Information Institute Wex.)

Plaintiff's first cause of action is for strict liability failure to warn. For strict product liability, a plaintiff must prove (1) the product has a specific inherent defect and (2) the defect in the product injured or damaged the plaintiff. There are three potential types of defect: (a) a manufacturing defect, where the product was not manufactured as intended; (b) a design design, where the problem is with the design of the product rather than how it was made; and (c) a failure to warn defect, where the manufacturer failed to warn about a reasonably foreseeable danger. (Cozen O'Connor, The Product Liability Torts.)

Here, plaintiff's counsel alleged that the defendant's filters contained warnings insufficient to alert consumers, including the plaintiff, of the dangerous risks associated with them.

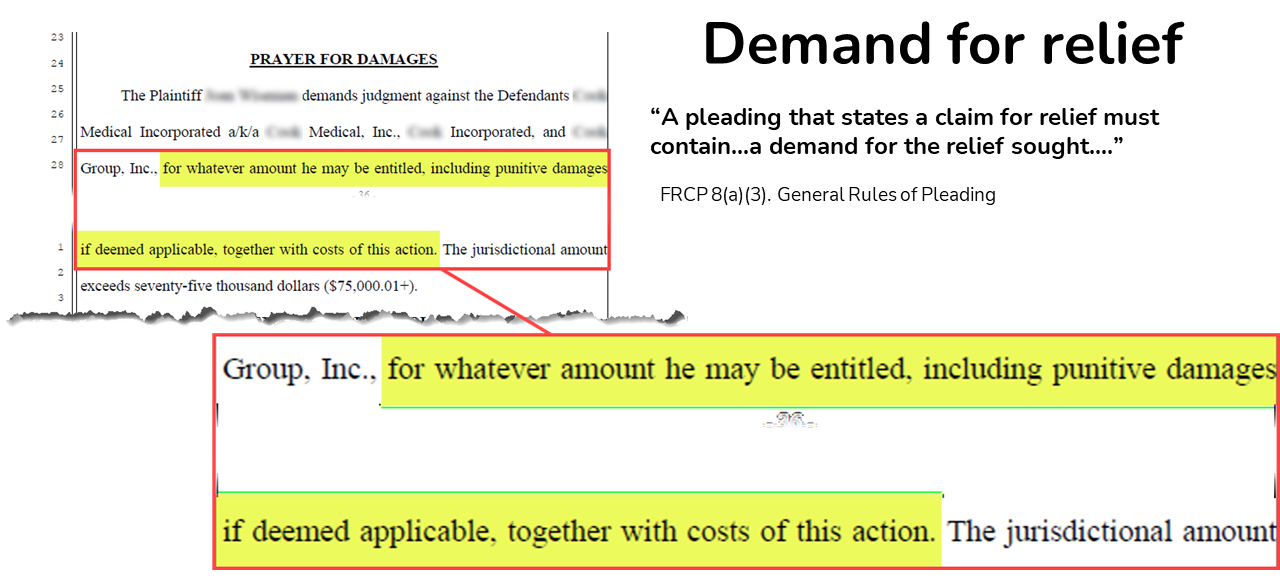

Demand or Prayer for Relief

The final required component of a complaint is the demand for relief. (FRCP 8(a)(3)). The demand, or prayer, for relief is where the plaintiff states the damages or other remedies sought from the court. (Legal Information institute Wex.)

The demand for relief often is simple, as is the case with this complaint, which states that "[t]he Plaintiff...demands judgment against the Defendants...for whatever amount he may be entitled, including punitive damages if deemed applicable, together with costs of this action."

Part 2: How AI can Help

In part 2, we will turn our focus to how you can use AI as you prepare a complaint, from the initial investigation into a potential matter to the final drafting of the complaint itself.